Somewhere in the shadowy corners of early American history lies a story we’ve nearly forgotten – the tale of Cofitachequi. This thriving Indigenous chiefdom emerged around 1300 CE in what’s now the southeastern United States, only to vanish by 1700 CE, leaving behind almost no trace. But one figure still haunts our historical imagination: The Lady of Cofitachequi.

We have no portraits of her. We don’t even know her real name. All we have are the scribbled notes in Spanish explorers’ journals – particularly Hernando de Soto, whose expedition stumbled into her territory in 1540. What they found shocked them to their core: a powerful woman ruling over a sophisticated society that defied everything they thought they knew about the “New World.” This impressive chiefdom flourished in what we now know as central South Carolina, with its heart likely centered along the Wateree River valley.

A Woman’s World: Power Through the Mother’s Line

Unlike the kings and queens of Europe, Cofitachequi belonged to the broader Mississippian culture – that network of remarkable mound-building societies that flourished across the Southeast from roughly 800 CE to 1600 CE. These weren’t simple villages but complex civilizations with cities, governance systems, and a political structure that ran through the maternal line.

Think about it – in these societies, your inheritance, your titles, your very place in the world came from your mother’s family. In a world without paternity tests, this made perfect sense – you always knew who your mother was. Women weren’t decorative figures in this world; they controlled property, influenced politics, and helped shape religious life.

The Lady of Cofitachequi wasn’t some anomaly or temporary stand-in. She was the natural outcome of a system that expected women to lead.

First Contact: A Welcome That Changed Everything

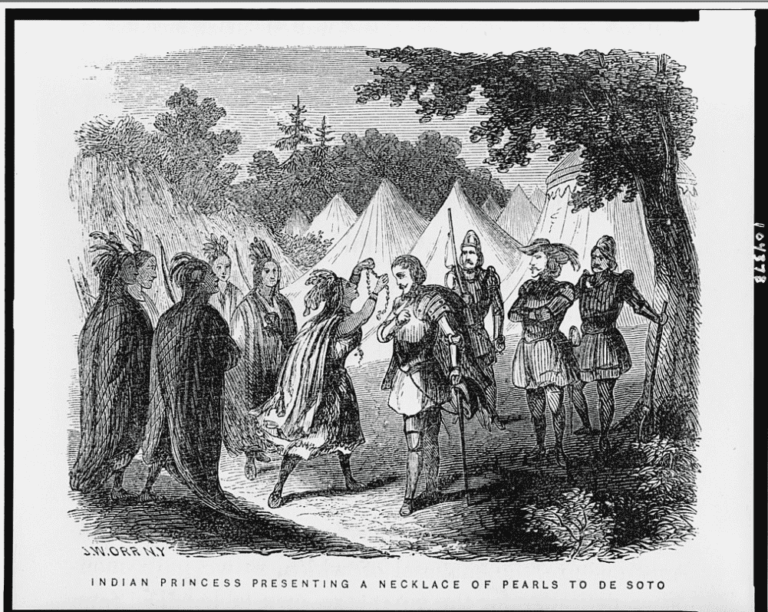

By the time de Soto arrived in 1540, his men were desperate souls – hungry, lost, and obsessed with finding gold. What they found at Cofitachequi must have seemed like a mirage: a refined, prosperous, peaceful city-state. And at its center stood a composed woman draped in pearls and fine cloth, who greeted them with unexpected dignity.

The Spanish couldn’t quite wrap their heads around it. The Lady offered them gifts and diplomacy, perhaps hoping to protect her people through careful negotiation. But her hospitality backfired. As tensions grew, she tried to escape, only to be captured by de Soto’s men who took her hostage as they pushed northwest toward the chiefdom of Joara. They likely saw her as a valuable asset for extracting resources or ensuring cooperation from other communities along their route.

But she wouldn’t play that role for long. In what must have been a daring act of resistance, she escaped into the wilderness with her servants, probably heading toward Talimeco, a nearby allied town. With that bold move – part practical escape, part symbolic rejection of Spanish authority – she disappears from written history.

We never hear from her again.

Early Spanish Interest

Cofitachequi may have appeared on Spain’s radar even before de Soto’s infamous visit. Back in 1521, Spanish ships anchored off what’s now South Carolina near Winyah Bay and kidnapped about 60 Indigenous people. Some mentioned a powerful leader called Datha or Duhare – possibly the Lady’s predecessor.

One captive, later known as Francisco Chicora, was taken all the way to Spain. After learning Spanish, he told the historian Peter Martyr incredible stories about his homeland. He described Datha as a tall, fair-skinned ruler carried everywhere by his subjects, overseeing a land dotted with ceremonial mounds, pearls, and prosperous cities like Xapira.

These fascinating stories helped launch the doomed 1526 expedition of Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, who tried to establish a colony in the region. The settlement collapsed after just three months, crushed by shipwrecks, disease, and Ayllón’s death. But it left behind European artifacts that likely made their way inland – perhaps explaining the European goods that de Soto’s men found at Cofitachequi fourteen years later.

A Glimpse Into the Mississippian World

The Mississippian culture created vast networks connecting trade, religion, and governance across the Southeast. Cofitachequi wasn’t isolated – it was a gleaming node in this web, established around 1300 CE and gradually abandoned by the early 1700s after centuries of colonial disruption.

These weren’t simple “tribes” as Europeans often labeled them. They were complex nations with hierarchical leadership, religious structures, and urban planning. Places like the Etowah Indian Mounds in Georgia – those massive earthworks that still rise from the landscape today – give us glimpses of this lost world. These ceremonial centers mirrored the political hubs that gave structure to life at Cofitachequi.

And the Lady? She wasn’t some historical oddity. She belonged to a tradition of influential women whose leadership shaped these societies – women whose stories were often misunderstood or completely erased by the very men who recorded them.

Beyond the Spanish Lens: Who Was She Really?

Despite de Soto’s accounts, so much about the Lady remains frustratingly unclear. The Spanish called her a “queen,” but that word flattens the complexity of her actual role. Was she a ruler in the European sense? A spiritual leader? A diplomatic representative?

Most likely, she was all these things – functioning within a matrilineal structure where community decisions often came through consensus, and where spiritual authority and political power weren’t neatly separated.

And then there’s the mystery of her disappearance. After fleeing from de Soto, she vanishes from the record. No name preserved. No confirmed descendants. It’s as if history itself swallowed her story.

The Slow Decline: Later Expeditions

Though the Lady’s personal story ended in mystery, Cofitachequi didn’t vanish overnight. Spanish explorers continued visiting the region. Between 1566 and 1568, Juan Pardo led a military expedition inland, referring to the region as Canosi – perhaps a new name for Cofitachequi.

Later, in 1627-1628, Captain Juan de Torres led two expeditions with a small Spanish force and Indigenous allies. He reported being warmly received by a local chief whose influence commanded respect throughout the region.

By 1670, the English had arrived. Explorer Henry Woodward journeyed inland from Charlestown and encountered Cofitachequi again. Its leader, whom he described as “the emperor,” commanded an impressive army of 1,000 bowmen and even made diplomatic visits to Charlestown in 1670 and 1672.

But the writing was on the wall. When John Lawson passed through in 1701, the capital was gone – replaced by smaller Congaree settlements, the remnants of a civilization that had once commanded both fear and respect.

Discoveries in the Soil: What We’re Finding Now

Though much about Cofitachequi has been lost to time, the earth still holds its secrets. In recent years, quiet archaeological efforts on private land have begun to confirm long-held suspicions about the location of the ancient capital. Remnants of indigenous pottery, ceremonial earthworks, and signs of early European contact have slowly emerged from the soil, offering tantalizing glimpses into the world the Lady once ruled.

The full story remains buried, waiting for careful hands—and open minds—to uncover it. Perhaps, somewhere beneath the layered earth, echoes of the Lady herself still linger, ready to step back into the light.

The Echoes That Remain

What ultimately happened to the Lady of Cofitachequi? We simply don’t know. And that absence – of her name, her voice, her people’s continuing story – speaks volumes about our historical blind spots.

Like so many Indigenous societies, Cofitachequi was devastated by waves of disease, warfare, and colonization. Did the Lady live long enough to witness her world transforming beyond recognition? Or did she pass away before the worst arrived?

Her silence mirrors the broader erasure of Indigenous memory. The Spanish saw her, but couldn’t truly understand her. Historians search for her, but find only fragments. Her story exists somewhere between myth, history, and silence – a presence we feel more than see.