When most people hear “Iroquois Confederacy,” they think of a powerful alliance of Indigenous nations in the Northeast and maybe a line or two in a history textbook about the Great Law of Peace.

But here’s what often gets left out: the real power behind one of the world’s oldest democracies didn’t just sit with the chiefs.

It sat with the women.

Way before women in Europe or colonial America could vote or even own land, Haudenosaunee women were calling the shots. They picked leaders. They removed them when they stopped doing their jobs. They managed family lines and oversaw land ownership.

These weren’t just caretakers. They were the backbone of the entire system.

They were the Mothers of Nations.

A Society Where Women Really Ran Things

The Haudenosaunee—more commonly known as the Iroquois—means “People of the Longhouse.” They formed a league of five nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca), with the Tuscarora joining later.

Their system of government was built around consensus, not coercion. Chiefs debated in councils, decisions were made thoughtfully, and everything was rooted in the Great Law of Peace, a constitution older than the U.S. itself.

But here’s the part that’s rarely mentioned: those chiefs didn’t get there on their own. Every one of them was nominated by a woman—a clan mother.

And if that chief ever stepped out of line or failed to represent the people with integrity, it was that same woman who had the power to remove him. They called it “removing his horns,” a symbolic way of stripping him of leadership.

Clan mothers weren’t behind the scenes. They were the ones pulling the levers.

The Peace Queen Who Helped Start It All

Long before the Confederacy was formed, the nations were at war—constant, violent war. Entire communities were unraveling.

And in the middle of all that, one woman chose peace.

Her name was Jigonsaseh, sometimes written Jikonhsaseh. Today, she’s often remembered as the Peace Queen. She lived in what’s now western New York, along the Genesee River, and opened her home to travelers—warriors, messengers, anyone moving through.

But there was one rule: leave your weapons at the door.

Inside her longhouse, peace was the law. And that space she created? It became the seed of something much bigger.

When the Great Peacemaker, a prophet determined to unite the warring nations, began his mission, Jigonsaseh offered her support. She believed in his message. She helped him connect with others. She gave his vision the grounding it needed.

She’s remembered as the first Mother of Nations—not just because she supported peace, but because she showed that lasting unity couldn’t happen without women at the center.

Want to see how it all unfolded?

Timeline: The Iroquois Confederacy and the ‘Mother of Nations’

~1000–1400 CE

Formation of distinct Haudenosaunee cultures and matrilineal clan systems~1100–1450 CE

Era of intertribal conflict; Jigonsaseh (Peace Queen) lives~1450–1600 CE

Founding of the Iroquois Confederacy; Great Law of Peace established1600s–1700s CE

Colonial contact begins; clan mothers maintain authority during upheaval1800s CE

Haudenosaunee women influence early U.S. women’s rights movement

What It Actually Meant to Be a Clan Mother

“Clan mother” might sound ceremonial or symbolic, but these women held serious power.

They chose the male chiefs who would represent their clans in the Grand Council—and they didn’t just hand out the job and step back. They watched closely. If a chief failed to live up to the responsibilities, the clan mother had the authority to remove him, no questions asked.

Beyond politics, they controlled lineage. They passed down clan names. They managed land rights. They kept family heritage alive—through the mother’s line.

This wasn’t permission granted by men. It was Haudenosaunee law. A chief who ignored his clan mother didn’t last long.

This wasn’t an exception to the rule. This was the rule.

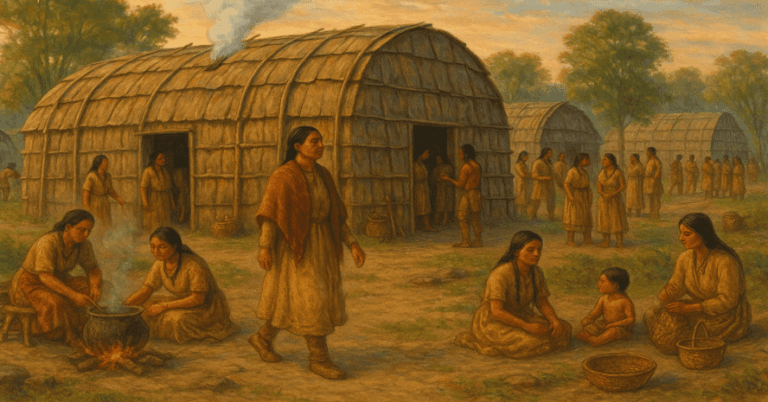

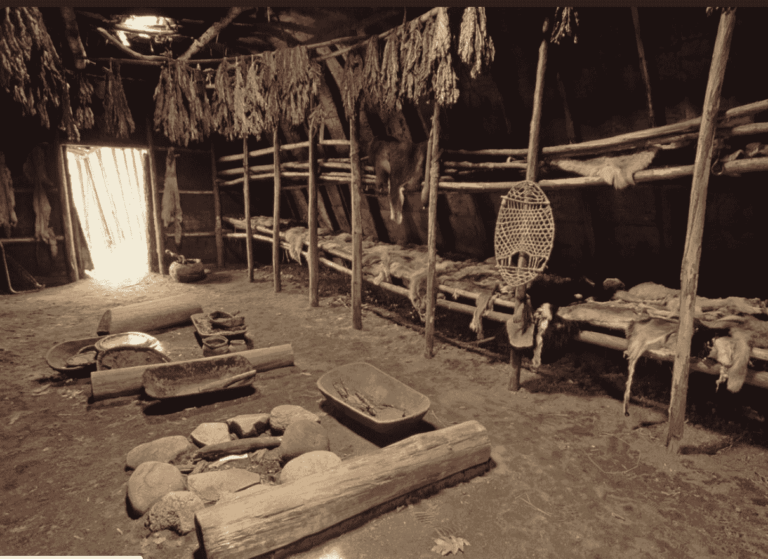

The Longhouse: Heart of the Community

To really understand the role of women in Haudenosaunee life, you need to picture the longhouse—not just as a building, but as a living symbol of the Confederacy.

Each family had their own section of the longhouse, grouped by clan. It wasn’t just about shelter. It was about community, cooperation, and continuity.

And it was the women who ran it all.

They owned the longhouses. They grew and preserved the food. They raised the children. They kept the social rhythm going, season after season.

In a world built on balance between people and the land, women were the stewards of both.

A Day in the Life: Stepping Into Her Shoes

Imagine this:

You’re a clan mother in the 1400s. The sun’s just rising. You’re stoking the fire in your longhouse while others sleep. Your day’s already begun.

You’ll check on the crops, prepare for a gathering, maybe teach your granddaughter how to weave. But that’s not all.

You’re also considering whether one of the men in your clan is ready to lead. If you support him, he could carry your clan’s voice into the Grand Council. If not, that’s the end of the conversation.

Later, there’s a women’s council meeting. A dispute needs settling. You’re expected to bring clarity—and history—to the discussion.

You don’t seek power. You are power, just like the women who came before you.

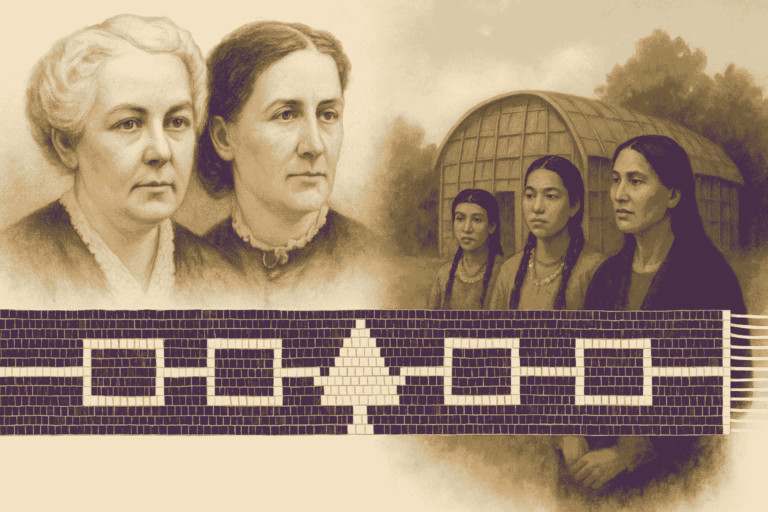

A Model for Feminists Centuries Later

By the 1800s, Haudenosaunee women were already living what American feminists were still dreaming about.

Leaders like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage saw it firsthand. They spent time with Haudenosaunee women, watched them make decisions, hold property, speak in councils, and raise their voices with confidence.

Gage even wrote that Indigenous women lived with “a degree of personal liberty unknown in the most advanced nations of the world.”

And where was the first Women’s Rights Convention held in 1848?

Seneca Falls.

Haudenosaunee territory.

Why Don’t We Hear More About This?

So why is this story so rarely taught?

Because it doesn’t fit the script.

A democracy shaped and sustained by women—before colonization—challenges the story Western civilization likes to tell about itself. It asks us to think differently about where real progress comes from.

And it proves that equality didn’t start with us.

In some places, we’re still catching up.

The Legacy Lives On

Even today, clan mothers still exist. Despite centuries of colonization, forced assimilation, and cultural erasure, the structure is still there.

Women still inherit clan identity. Still name the chiefs. Still carry the teachings of the Great Law of Peace.

Yet outside Haudenosaunee communities, their role is barely mentioned. People remember the Iroquois for their warriors and treaties—not the women who made all of it possible.

But the truth is: they kept the peace. They chose the leaders. They passed down a system of governance that predates the U.S. and outlasted empires.

One Last Thought

What if we stopped seeing women as helpers to history—and started seeing them as its architects?

The title “Mother of Nations” isn’t just poetic. It’s earned.

These women created space for peace in a time of war. They built something that lasted. And they did it not through force—but through fire-tending, wisdom-sharing, and leader-choosing.

Maybe that’s why it’s so easy to forget.

Because real power doesn’t always shout.

Sometimes, it just names the next chief.