It sounds like something out of a science fiction novel: a sunken city, hidden beneath the ocean for what could be over 140,000 years old. But that’s exactly what a team of researchers believes they’ve found—and if they’re right, this discovery could change everything we thought we knew about human history.

The remains of the city were spotted deep under the sea, in a location in the Madura Strait between the islands of Java and Madura.

What’s clear, though, is that this wasn’t some random pile of rocks. The layout hints at something far more intentional: roads, structures, perhaps even communal gathering spots. In short, it looks like a place where people once lived—and lived well.

What’s especially striking is the age of it all. At 140,000 years old, this city would predate every known civilization by tens of thousands of years. That kind of timeline forces a hard look at what early humans were capable of. Could they really have built cities this complex so far back in time? With every new scan and sonar image, that story is slowly being pieced together.

Oddly enough, the ocean may have done this place a favor. Being submerged for so long has actually helped preserve parts of it. With little exposure to the elements—and to modern interference—the city is offering researchers a rare glimpse into a deeply buried past.

The discovery has sparked excitement and a fair share of debate. If this really is what it appears to be, then the history of organized human society may need a serious rewrite.

For over a decade, a collection of fossilized bones sat largely overlooked, tucked away after being pulled from the seafloor by sand miners off the coast of Southeast Asia. Now, those bones are being analyzed and are potentially rewriting what we know about an ancient world that once existed where the sea now rolls—a massive land of tropical plains known as Sundaland.

As you can see in the image above, the lighter color areas are where the land was once above water, and these islands were all connected as one giant land mass.

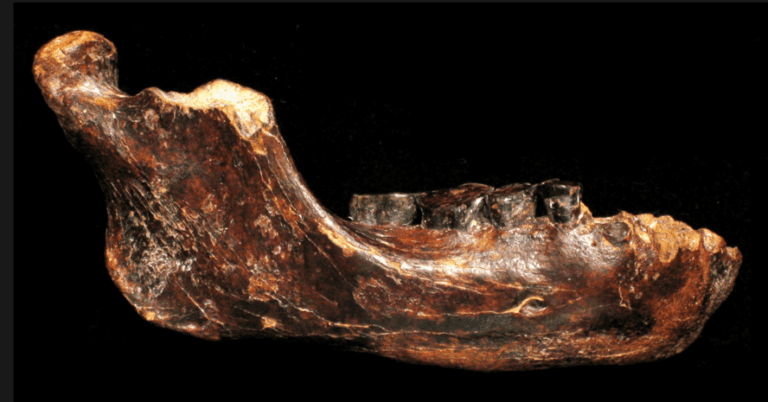

The remains, recovered by maritime sand miners in the Madura Strait back in 2011, sat unexamined for years. Recently, a team of researchers led by Harold Berghuis of the University of Leiden has confirmed that the collection—over 6,000 fossils in total—includes skull fragments of ancient hominins, along with bones from 36 animal species such as buffalo, deer, elephants, and Komodo dragons.

Crucially, many of the animal bones bear deliberate cut marks, offering rare evidence of early human hunting practices. These marks point to the presence of hominin groups who were not only capable of but actively engaged in systematic hunting—far earlier than previously documented in this part of the world.

This study provides the first tangible evidence that Homo erectus or related early human species once inhabited Sundaland before it was overtaken by rising seas. It challenges long-standing assumptions that early hominin populations in the region were geographically limited and stationary. It paints a picture of a population that wasn’t just surviving, but adapting intelligently to its environment.

“This period is characterized by great morphological diversity and mobility of hominin populations in the region,” explained Harold Berghuis, the lead archaeologist from the University of Leiden in the Netherlands. His team’s work has placed the remains in a timeframe that suggests humans were living in and moving through this landscape far earlier than once believed.

The discovery doesn’t just expand our understanding of human evolution—it hints at a whole way of life that vanished beneath rising seas thousands of years ago. Sundaland, once a sprawling plain of rivers, forests, and fertile valleys, is now almost entirely underwater. But through findings like this, its story is beginning to surface.

For scientists, it’s a rare glimpse into how early humans may have responded to dramatic environmental changes—changes that eventually submerged their world. For the rest of us, it’s a powerful reminder of how much history connecting us to the Ice Age still sleeps beneath the ocean floor.

Between 14,000 and 7,000 years ago, melting glaciers raised global sea levels by more than 120 meters (roughly 400 feet), drowning the low-lying plains of Sundaland and forcing prehistoric communities to migrate inland or to higher islands. This dramatic environmental shift may have played a key role in shaping patterns of human dispersal across Southeast Asia.

“These findings reveal the great mobility and morphological diversity of hominin populations in the region,” Berghuis said. “And they show the importance of submerged landscapes in understanding the broader human story.”

Using a combination of archaeological, geological, and paleoenvironmental techniques, the team was able to reconstruct not only the age and species of the fossils but also the broader environmental context in which these early humans lived. The research demonstrates how interdisciplinary methods can unlock hidden chapters of human history preserved beneath the sea.

The fossils from the Madura Strait are just one part of a much larger puzzle—one that spans continents and tens of thousands of years. As underwater exploration technology continues to improve, scientists hope to uncover more evidence of ancient cities, farming communities, and lost cultural memory buried beneath the oceans.

This discovery marks a milestone in the study of human origins in Southeast Asia—and suggests that some of our oldest stories may still lie hidden beneath the waves.